Author

Reviewer

Share Article

Dyslipidemia Management in Primary Care

This blog covers topics of interest to primary care providers from the 2021 Endocrine Reviews paper "A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia" co-authored by Dr. Amanda Berberich and myself. We wrote this paper to provide a “one-stop shopping experience” for current lipid needs. Full details are at this link to the free article: https://academic.oup.com/edrv/article/43/4/611/6408399

| Author | Reviewer |

|

Robert Hegele, MD, FRCPC |

Milan Gupta, MD, FRCPC, FCCS, CPC(HC) |

What’s the bird’s eye view of this article?

We try to concisely and accurately update the clinical approach to dyslipidemia.  We underline what’s worth keeping from the past, but also highlight new developments, including a streamlined classification system, a pragmatic approach to patients with high cholesterol or triglycerides, the potential role of genetic testing, apo B and Lp(a), as well as covering current and emerging treatments. Here’s the graphical abstract:

We underline what’s worth keeping from the past, but also highlight new developments, including a streamlined classification system, a pragmatic approach to patients with high cholesterol or triglycerides, the potential role of genetic testing, apo B and Lp(a), as well as covering current and emerging treatments. Here’s the graphical abstract:

What’s worth keeping from the past?

The foundation of management remains lifestyle advice: weight maintenance through diet and exercise. Occasionally, this can completely correct the dyslipidemia but typically it allows for medications to be used at lower doses. General dietary advice includes: 1) reduce intake and portion sizes; 2) replace high glycemic index foods with complex carbohydrates; 3) reduce trans and saturated fats; 4) choose lean meat like fish or poultry; 5) add foods that can benefit the lipid profile, such as soluble fibre and plant sterols; and 6) eliminate alcohol in patients with very high triglycerides.

Exercise intensity depends on the patient’s health and fitness. Adults and children with no restrictions can aim for 30 to 60 minutes of moderately intense activity three to five times per week (total 150 minutes/week), with adjustments for less fit patients. Exercise helps caloric balance, blunts weight gain, increases insulin sensitivity, and promotes lipoprotein catabolism.

How do we classify dyslipidemias?

It’s time to ditch the complicated classification of lipid disorders from medical school. Instead, dyslipidemia definitions can be streamlined into four categories: 1) hypercholesterolemia; 2) hypertriglyceridemia; 3) combined dyslipidemia; and 4) others, such as low HDL-C or high Lp(a).

![]() Which patients should I use PCSK9 inhibitors for and when?

Which patients should I use PCSK9 inhibitors for and when?

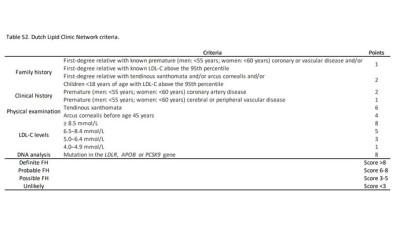

What about genetic dyslipidemias?

There are 25 named genetic dyslipidemias, most of which are extremely rare. The exception is heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH), which affects ~1 in 300 Canadians, with higher prevalence among Francophones. FH responds well to treatment – numbers needed to treat are 3-5 FH patients to prevent one cardiovascular event over 10 years.  Therefore, it’s important to make the diagnosis and to start treatment early. Clinical assessment includes checking for corneal arcus, xanthelasmas, and tendon xanthomas. Because FH is genetic determined, screening of close relatives has a high yield of finding new cases. FH is clinically diagnosed using online FH scoring tools, such as: Genetic testing, already available in Quebec and being piloted in other provinces starting in 2023, helps make a definitive FH diagnosis, but it’s not absolutely essential. PCSK9 inhibitors have tremendously helped the FH population attain strict LDL-C thresholds for the first time in their lives.

Therefore, it’s important to make the diagnosis and to start treatment early. Clinical assessment includes checking for corneal arcus, xanthelasmas, and tendon xanthomas. Because FH is genetic determined, screening of close relatives has a high yield of finding new cases. FH is clinically diagnosed using online FH scoring tools, such as: Genetic testing, already available in Quebec and being piloted in other provinces starting in 2023, helps make a definitive FH diagnosis, but it’s not absolutely essential. PCSK9 inhibitors have tremendously helped the FH population attain strict LDL-C thresholds for the first time in their lives.

Why are we still talking about hypertension?

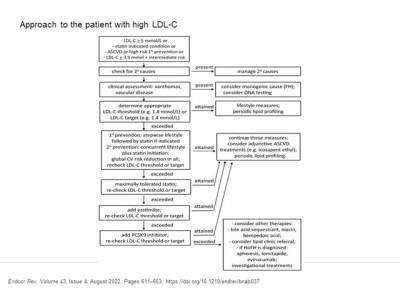

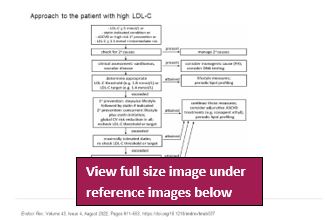

How do I approach the patient with high LDL cholesterol?

Our pragmatic approach for hypercholesterolemia builds on algorithms from the 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society lipid guidelines:

A nonfasting lipid profile is a great screening test, since ~90% of patients don’t have triglycerides high enough to interfere with LDL-C, especially with newer lab methods recently implemented across Canada. When non-fasting triglycerides exceed 4.5 mmol/L, a lipid profile should be repeated with fasting. When LDL-C is high, secondary causes – e.g. diet high in trans or saturated fats, hypothyroidism, cholestatic liver disease or nephrotic syndrome – must first be ruled out and managed if appropriate. A family history of dyslipidemia and/or early atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) should be sought to stratify risk. Physical examination targets the cardiovascular system and systems associated with secondary causes, while also screening for signs of FH.

A nonfasting lipid profile is a great screening test, since ~90% of patients don’t have triglycerides high enough to interfere with LDL-C, especially with newer lab methods recently implemented across Canada. When non-fasting triglycerides exceed 4.5 mmol/L, a lipid profile should be repeated with fasting. When LDL-C is high, secondary causes – e.g. diet high in trans or saturated fats, hypothyroidism, cholestatic liver disease or nephrotic syndrome – must first be ruled out and managed if appropriate. A family history of dyslipidemia and/or early atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) should be sought to stratify risk. Physical examination targets the cardiovascular system and systems associated with secondary causes, while also screening for signs of FH.

What can natriuretic peptide testing tell me about my heart failure patients?

When is medication necessary for my patient with hypercholesterolemia?

The maximally tolerated dose of a high intensity statin (i.e. rosuvastatin or atorvastatin) is recommended as first-line treatment for secondary prevention in those with known ASCVD. For primary prevention, statin-indicated condiitons include diabetes, renal impairment, or abdominal aortic aneurysm. Also in primary prevention, statin treatment is a consideration if LDL-C > 3.5 mmol/L in a patient with intermediate ASCVD risk, and if LDL-C > 5.0 mmol/L in a patient with no risk factors. For patients whose LDL-C levels do not warrant treatment, or if LDL-C are inaccurate due to high TG levels, clinical action is also justifiable based on either apo B or non-HDL-C – where threshold levels in high risk patients are 0.7 g/L and 2.4 mmol/L, respectively.

For those who exceed their threshold on maximally tolerated statin, adding additional agents, either ezetimibe in primary prevention or when LDL-C is relatively close to the threshold, or PCSK9 inhibitors in those at high risk, especially with existing ASCVD and requiring greater LDL-C lowering. The general principle of managing LDL-C is that “lower is better,” with no negative effects even with extremely low LDL-C in clinical trials of evolocumab. There is no need to de-intensify treatment in those who attain very low LDL-C levels.

![]() How has COVID-19 impacted Canadians with cardiovascular disease?

How has COVID-19 impacted Canadians with cardiovascular disease?

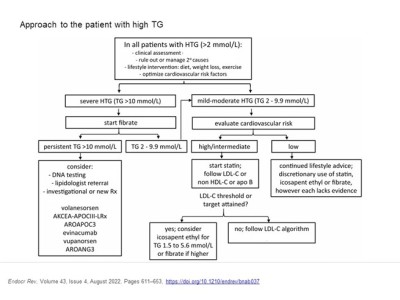

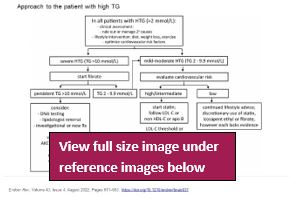

How do I approach the patient with elevated triglycerides?

Our algorithm for adults with newly diagnosed hypertriglyceridemia breaks down into mild-to-moderate and severe hypertriglyceridemia:

First, screen for secondary causes such as  obesity, metabolic syndrome, diet rich in calories, fat or simple sugars, alcohol, type 2 diabetes, uremia, proteinuria, pregnancy (mainly the third trimester), paraproteinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus. Medications that raise triglycerides include corticosteroids, oral estrogen, tamoxifen, thiazides, non-cardioselective beta-blockers, bile acid sequestrants, cyclophosphamide, antiretroviral drugs, and second-generation antipsychotic agents. Identifying and addressing secondary causes can sometimes dramatically improve hypertriglyceridemia.

obesity, metabolic syndrome, diet rich in calories, fat or simple sugars, alcohol, type 2 diabetes, uremia, proteinuria, pregnancy (mainly the third trimester), paraproteinemia, or systemic lupus erythematosus. Medications that raise triglycerides include corticosteroids, oral estrogen, tamoxifen, thiazides, non-cardioselective beta-blockers, bile acid sequestrants, cyclophosphamide, antiretroviral drugs, and second-generation antipsychotic agents. Identifying and addressing secondary causes can sometimes dramatically improve hypertriglyceridemia.

Once secondary causes are ruled out, repeated fasting triglycerides > 10 mmol/L signal high risk for pancreatitis and a situation that calls for fibrate treatment. For patients with triglycerides between 2 and 9.9 mmol/L, the primary medical concern is ASCVD, so risk factors must be managed. Medications with proven cardiovascular benefit, such as statins, ezetimibe and icosapent ethyl, are preferred pharmacological treatments. Unfortunately, fibrates show no incremental ASCVD benefit when added to background statin therapy in mild-to-moderate hypertriglyceridemia. Because LDL-C may not be accurately measured in a statin-treated patient with persistently elevated triglyceride, non HDL-C or apo B are alternative tests for treatment thresholds and for monitoring the effects of therapy.

Any final words?

For those who’re interested, our article details how and when to order apo B and Lp(a), and covers the exciting new RNA knock-down drugs for hypertriglyceridemia, combined hyperlipidemia and elevated Lp(a) levels, which are being evaluated in randomized CV outcome trials. These topics warrant their own blog. Finally, we circle back to the cornerstones, namely identifying secondary factors, global risk factor control and lifestyle management, as well as implementing evidence-based therapies.

The development of this blog was overseen by the Canadian Collaborative Research Network and was supported through an educational grant from Amgen.

References

- Berberich AJ, Hegele RA. A Modern Approach to Dyslipidemia. Endocrine Reviews 2022 Jul 13; 43: 611-653.

- Pearson GJ, Thanassoulis G, Anderson TJ, et al. 2021 Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Adults. Can J Cardiol. 2021 Aug; 37:1129-1150.

- Defesche JC, Gidding SS, Harada-Shiba M, et al. Familial hypercholesterolaemia. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017 Dec 7;3:17093.

Reference Images

copyright © 2026 CCRN

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of CCRN.